Gregory Crane

Tufts University

A Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) can allow citizens to pursue any subject at any depth, without compromise, from the casual curiosity of the moment through study that may last a lifetime. This document outlines this vision, points to communities, collections and services available now that could be included in a prototype for a DPLA, and suggests some contributions to be made within the context of a prototype phase.

A DPLA can enable all libraries in the United States – public libraries, school libraries and the libraries of higher education as well – to foster intellectual activity from childhood throughout life, empowering each individual to explore without any compromise any subject at any depth – whether that exploration is the curiosity of a moment or evolves into a settled interest that enriches the individual’s life for decades. In supporting such individual growth, we can also reinvigorate our cultural institutions and intellectual communities, drawing upon the digital medium not only to support virtual connections but also to increase the face-to-face relationships both within and across existing institutions. Vast collections have taken shape and new services have been developed that illustrate the human record in ways that were inconceivable in the 19th century. The raw materials for a DPLA are already in place. For humanists, the DPLA is both an opportunity – and a challenge – to rethink the education that we provide and the research that we conduct.

Fostering curiosity and intellectual development reasserts one of the foundational ideas that led the creation of public libraries within the United States – ideas that still find expression in the architecture of some public libraries. A DPLA is thus both a radical innovation and an assertion of ancient democratic values central to the development of the United States.

Figure 1: Reading Rooms in Public Libraries. The images above are of the reading room in the Robbins Library (built in 1892) in Arlington, MA, a suburb of Boston, a building given to the town of then 5,200 with a capacity of 60,000 volumes. The Renaissance design included paintings of historical events (the return of Columbus is visible in the right most image of the left hand picture) The net public can now access 3,000,000 digitized volumes from Gallica, Google, and the Internet Archive – fifty times as many as the original Robbins Library could contain. How can such vast collections serve local communities such as the one that frequents the Robbins Library today?

The role of the public library is clearly stated in the Latin motto visible above in the central portrait hanging on the wall in the left-side image of Figure 1 and as a detail above in the right-side image: “our ancestral inheritance is the defense of liberty.” The date makes the cultural reference more precise: the British forces, in their retreat from the battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, inflicted sharp casualties on civilians near the current site of the Arlington Robbins Library.

The public libraries that emerged in 19th century America reflected a shift away from the indirect democratic model, with its limitation on voting and roots in the Roman Republic, and towards the more direct democracy represented by Athens.

Figure 2: Greek Revival: The 19th century German painter Philipp von Foltz envisioned Pericles’ funeral oration. The reemphasis on Greek culture, which began in Germany, spread to the United States, especially as Americans such as Edward Everett (trustee of the Boston Public Library) began to study in Germany. This intellectual shift manifested itself in Greek Revival houses, such as the Whittemore house in Arlington (pictured above), which appeared in the 1840s. A decade later this strengthening commitment to democracy led to the creation of free public libraries such as the Boston Public Library.

When, more than two thousand years ago, Athenians developed a participatory democracy, they saw in this a system that energized its citizens like no other. Shortly after the rise of their democracy in the sixth century, the Athenians shocked their neighboring states with an energy born of their sense that each citizen could contribute. A generation later, the Athenians shocked the world by leading an alliance that defeated an invasion by Persian Empire, the sole superpower of the time. Another generation later, as the Athenians began a thirty-year civil war within the Greek world, we have an account of the funeral oration of Pericles, the pre-eminent statesman of his generation, which describes those ideas that separated democratic Athens from its competitors. Pericles argues that democracy allows its citizens to more fully realize their gifts and aspirations and to explore their own interests with a freedom and a depth that subjects of no other system could approach.

Figure 3: Public programming from the Long Beach Island, NJ, and Lexington, MA. A DPLA can transform the ability of local residents to explore topics such as those above.

A DPLA consequently offers the United States a historic opportunity because it allows us to seize upon the new potential of the digital world to assert this ancient goal more fully. Pericles boasted that Athens had become the school for the Greek world. The DPLA will allow the United States not only to transform the intellectual life of its citizens but also to rearticulate a position of leadership beyond military force and based upon the reassertion of its core democratic values within a shifting world.

In addition, the DPLA can provide a common space within which the 12,000 public libraries, 100,000 libraries in primary and secondary schools, and 3,200 academic libraries can serve each of their traditional constituencies in ways that were never before feasible. Citizens of the United States have an opportunity to develop their interests across more subjects and at greater depth than has ever been possible before. Equally important, the DPLA can provide a common space in which patrons are also citizens, who have opportunities not only to learn but also to contribute back to our evolving understanding.

In 2011, the net public has access to millions of sources from the human record produced in hundreds of languages and providing information about every culture that left its impression within the written record. In effect, not only public libraries but also libraries in primary and secondary schools, in colleges and universities, historical societies and museums, all have vast and rapidly growing holdings. While copyright poses major challenges to the general distribution of popular film, books and games, these issues for the most part affect less than 100 out of more than 4000 years of the human record – works from almost 98% of the period from which our sources survive are in the public domain.

For higher education the DPLA poses both a challenge and an opportunity, for it can provide a structured environment within which students and faculty can interact with every aspect of society. For humanists such a change offers profound opportunities with which to realize their goal of advancing intellectual life of society as a whole. Rather than developing ideas and resources that circulate within a few thousand (and usually a few hundred) academic libraries and customarily reach only a specialist audience, humanists can now contribute to a network of resources. This enables more members of society to think more deeply about, and, often for the first time, to make contributions to our understanding of the human past and how we wish to fashion the future.

This transformation demands a decentralized intellectual culture very different from the specialist conversations of 20th century academia. Humanists must rethink not only their audiences but also their collaborators. There are millions of original sources, visual as well as textual, already publicly accessible in digital format and these far exceed what advanced researchers and library professionals can interpret, much less document in a way that makes them intellectually accessible for non-specialists. We need to enlist a generation of student researchers and citizen scholars who work side by side as partners with the limited number of advanced researchers and library professionals. This represents a vast redistribution of authority – and of responsibility as well.

Student researchers and citizen scholars pose complementary groups. Students have the opportunity to devote sustained periods of time acquiring knowledge and developing skills within a structured environment. The DPLA thus provides students with a venue to which they can make tangible and increasingly sophisticated contributions from their first introductory classes onwards. While citizen scholars may or may not build upon skills acquired in a structured academic environment they can nonetheless explore subjects such as local history, represent the knowledge of communities that do not have significant representation in formal academic discourse and develop their contributions over decades. The DPLA can therefore provide an environment where the instructor, the library professional, the student, and the citizen scholar each interacts with the other, accomplishing as a community far more than any one could do on their own, with each living a more dynamic and satisfying intellectual life than would otherwise be feasible.

Our core use case is general: Patrons of a library encounter something from popular media that captures their imagination and a visit to Wikipedia or a similar site only increases their curiosity and they want to understand how we know what we know.

Print and broadcast media provide members of society with content to capture their imagination – films and television series about the past, both fictional and documentary, historical novels and even detective novels set in earlier periods, bring the past to life and arouse curiosity. The Civil War, Shakespeare, the American Revolution, the history of technology and other topics excite passionate interest. Each of these plays critical role in the contributions that we hope to make to a future DPLA.

We consider here as a general example the ancient Greco-Roman world for a number of reasons. First, it remains a major source for every form of popular medium – fiction and non-fiction, film and prose. Second, the sources about the ancient Greco-Roman world are particularly challenging to work with – the original sources are in Classical Greek and Latin, and our knowledge about the Greco-Roman world has appeared in every written language from areas spanning from Morocco to Afghanistan. The physical world of Greece and Rome has left impressive remains behind to this day but we must reconstruct our understanding of this physical world from archaeological finds spread across thousands of miles. Third, a great deal of work has gone into developing open content collections and open source services needed to locate and then to understand the sources behind our understanding of the Greco-Roman world. Fourth, the new decentralized culture of intellectual life has taken hold among students of the Greco-Roman world, with student researchers emerging as key participants in colleges and universities in the United States and Canada.

Figure 4: In the Tanglewood Tales (far left), Nathaniel Hawthorne retold Greek myths for children as the Boston Public Library was pioneering the concept of a free public library in the mid-19th century. These stories continue to be retold in books and film.

Figure 5: The Ancient World and Popular Culture. (from above left) The 2004 movie Troy was one of four hundred films set in the Greco-Roman world and produced in the last hundred years, including nine that have ranked among the biggest moneymakers of all time; the Greco-Roman world plays a prominent role in historical documentaries broadcast on networks such as National Geographic, History, and Discovery. Historical fiction set in the ancient world has a long history (the Civil War general Lew Wallace wrote Ben Hur) and popular authors such as Colleen McCullough have continued to interpret ancient history as the subject for modern fiction.

A great deal of work has been done to make the sources behind writing and film about the ancient world accessible.

Figure 6: The Cambridge Ancient History at the Lexington, MA, public library. American public libraries often provide the basic materials whereby an interested audience can find some of the sources behind the books and films described above. A general reference work such as the Cambridge Ancient History provides one overview of Greek and Roman history, with footnotes that include not only modern discussion but also citations by which readers can find the sources upon which the modern discussion is based.

Figure 7: Sources on Greek and Latin culture on the shelves of the Arlington, MA, Robbins Library. The red volumes on the lower right in the left hand image are from the Loeb Classical Library, a series founded by the banker James Loeb to make Greek and Latin sources accessible to a broader audience. Each volume contains an original source text in Greek or Latin on the left hand page, along with an English translation on the right. Determined viewers of a film such as Alexander or a documentary such as When Rome Ruled or the reader of a novel such as First Man in Rome could find some of the background for some of the topics that they had encountered in their libraries. Nonetheless a number of problems still stand in the way, for only a subset of the relevant sources is normally available in a public library. In addition, citations such as “Tacitus, Ann. III, 70” (Chapter 70 of Book 3 of the Annales, a historical work by Tacitus) assume a prior knowledge of how canonical sources are organized. Finally, when contextualizing materials are available, they may not address the needs of a non-specialist audience (footnote 1 of the Loeb page above, for example, contains an un-translated Latin quotation).

An eighteen month prototype phase for a DPLA can accomplish a great deal by building on foundations already in place: collections, services, and communities already exist that can be exploited where possible, rebuilt when necessary, and integrated together into a larger whole that not only improves upon the parts but that makes the vision of the DPLA in 2011 a compelling and tangible incipient reality in 2013. A great deal will remain to be done but the direction will be clear and the journey well underway. The following describes existing communities, collections, and services that can play a role.

Public libraries exist not only to serve individuals but also to strengthen and even to create communities, and, in so doing, to foster a democratic society. A DPLA is valuable insofar only as it advances individuals, communities of interest and society as a whole. The DPLA thus has the opportunity to transform the role that libraries can play in society by creating dynamic connections between previously isolated networks of public, school and academic libraries, providing a virtual space that enhances the physically and institutionally linked communities that public, school and academic libraries each individually and distinctively serve.

Our group in particular can help transform the role of higher education within the DPLA – in fact, we believe that the DPLA can provide a new and far more effective space within which to develop and disseminate complex ideas and to advance the intellectual life of society. The DPLA thus can increase the range of the most advanced researchers while engaging a far broader segment of society. For the participants at Tufts University in particular, the DPLA provides an opportunity for that active citizenship that the Tisch College of Citizenship and Public Service is designed to promote among its students.

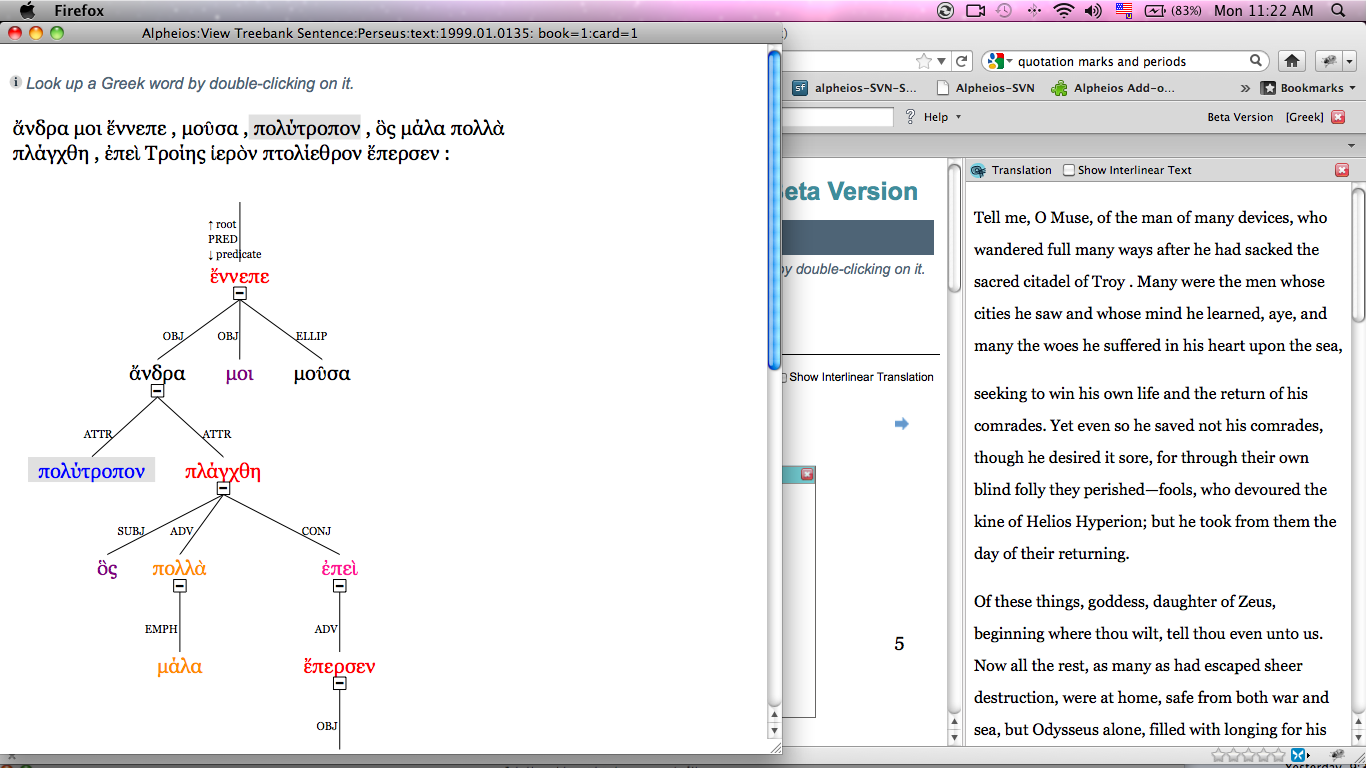

Classics faculty and students represent a particularly well-developed and cohesive group. The Homer Multitext Project (http://chs75.chs.harvard.edu/manuscripts/), led by the Center for Hellenic Studies in Washington, DC, engages undergraduates and faculty at Furman University, College of the Holy Cross, and the University of Houston in creating digital editions of complex manuscripts for the Homeric epics – a stunning demonstration of how student researchers working as a team can produce demonstrably more accurate and extensive results than individual experts working in isolation. In a similar vein, hundreds of students and faculty from North America and Europe, working together produced the Greek and Latin treebanks (http://nlp.perseus.tufts.edu/syntax/treebank/)– databases of syntactically analyzed texts that are the equivalent of genomes for the study of language. In addition, faculty and students of classics at institutions such as the University of Chicago, Harvard University, Mount Allison University, Tufts University, and the University of Missouri at Kansas City are working together on open source digital projects that will reach well beyond the research community.

We need to engage the K-12 community within the DPLA as well. Examples such as Liberty’s Kids (http://libertyskids.com), Percy Jackson and the Olympians (http://www.percyjackson.com), and the Kane Chronicles (http://www.rickriordan.com/my-books/kane-chronicles.aspx) illustrate the continuing hold of subjects such as American history, Greek Mythology and Ancient Egypt upon a younger audience. To cite one particularly interesting project, archives in two Mississippi cities partnered with local schools not only to engage students, but also to showcase the vitality of local records with the community. “Tales from the Crypt” (launched in 1991) assigns high school juniors the task of researching individuals buried in a Columbus graveyard. With only a list of names, the students use the primary and secondary sources available at the Columbus-Lowndes Public Library Local History Room and create a vignette on their individual for a performance in the cemetery. Inspired by the initiative, Jennifer Rose, archivist at the Sunflower County Library System, began “Headstone Stories” in 2010 and successfully incorporated a similar program into her community. More than 350 research papers by former students now housed in the local history department of Columbus-Lowndes Public Library provide a great resource for other patrons conducting genealogical research.1 The DPLA could provide a space that could make such existing efforts visible to a national audience while also providing tangible incentives to inspire more such projects around the country.

Where the DPLA can enhance the already extensive infrastructures of K-12 and postsecondary education, it has the potential to transform the ability of largely volunteer-driven organizations, such as local historical societies, Civil War roundtables, historic houses, and small museums to produce, to disseminate and to preserve their work. Many such organizations exist in the Boston area and these can provide a relatively easy starting point for what must rapidly become a national discussion.

The greatest challenge for a DPLA lies outside of the sectors of K-12, higher education and local cultural organizations. No DPLA can serve or represent America unless Native American communities are also able to represent their own histories and cultures. Native American communities represent sovereign nations with their own languages and with very different perspectives on how to share their cultures with society as a whole. The Protocols for Native American Archival Materials (http://www2.nau.edu/libnap-p/) have provided instruments whereby to establish productive relationships between Native American communities and other groups. The Mukurtu Project (http://www.mukurtuarchive.org/), also mentioned below) has begun to encode in an open-source content management system some of the digital protocols by which Native American communities can begin to share their heritage in culturally appropriate ways. At the same time, the Smithsonian Institution has begun an attempt to transform its own relationship to Native American peoples,2 an effort on which the DPLA should build.

Our contribution to the DPLA Prototype focuses on three complementary categories of collection.

We assume access to a relatively small number of commercially viable copyrighted works (e.g., movies, television series, documentaries, novels, mysteries) that serve to capture the imagination. While the electronic licenses have raised serious issues for libraries, many libraries have mechanisms in place that, at least for now, provide their patrons with access to a range of copyrighted materials. Our effort can begin immediately while other components of the DPLA Prototype address the long-term rights issues.

We build upon access to millions of digitized open content sources, including millions of digitized books and many millions of images of people, places and artifacts that are available in relatively stable organizations and with reasonably documented provenance. In the past, patrons of public and school libraries might have had access to tens of thousands of books while only a relative handful of students and faculty in higher education had access to as many as a million books. Three million public domain digitized books and manuscripts are available today for download from the French Gallica digital library (http://gallica.bnf.fr/?lang=EN), from Google Books (http://books.google.com) and from the Internet Archive (http://www.archive.org). A great deal more needs to be done as we augment these collections but a critical mass of source material already exists for a growing body of sources.

We focus, however, primarily upon enabling the production of new content that challenges the public to contribute as well as to consume. New content can consist of a correction of a single OCR error (e.g., changing “lie said” to “he said”), of marking chapter breaks or quoted poetry, of labeling people and places or adding complex linguistic markup to make a non-English source text more accessible. Content can include the introductions, explanatory notes, and other contextualizing materials. It can also include studies of particular people, organizations or other topics enabled by access to a huge and growing collection. Anyone can contribute – if the reader of an English translation associates a particular place name with a particular place (e.g., Rome with Rome, Georgia, USA vs. Rome, Italy), that annotation can be applied automatically to the original language source. And contributions can sustain years of learning and intellectual development. Contributing to the DPLA thus can provide citizens with an opportunity to learn how to contribute to a digital culture and economy.

Curated collections are available for the ancient world (virtually every surviving source about the Greco-Roman world has been digitized by Google Books and/or the Internet Archive, while TEI XML transcriptions and English translations exist for the vast majority of the most important sources) and for five centuries of print culture. We particularly emphasize the existence of TEI-encoded collections on Shakespeare and the Early Modern Period, the American Civil War histories and newspapers (including the Richmond Times Dispatch and William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator) and on local history in the Boston area (with examples of encoded town histories, directories, gazetteers and other common document types).

For archaeology, we point to the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), which has made more than 1 million images of ancient objects available via the database Arachne (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arachne(Archaeological_Database). The DAI and Perseus are partners in a DFG/NEH grant to make these collections more accessible to an American audience, a grant that opens a wide range of opportunities for American contributors.

A DPLA must focus upon the logical units of interest to its patrons. The major work of the DPLA only begins when the patron has found an item of interest – whether that item is a short story, a poem, a recording, a video, or similar object. Traditional library systems have focused upon providing physical access to an artifact. While users now have physical access to millions of downloadable books, simply obtaining a poem in Arabic or even an 18th century document in English on the American Revolution does not provide intellectual access. The DPLA must provide services for the following:

Catalogues that cover every word of every book in the library – readers read one word and one paragraph at a time. If readers are working through Moby Dick, they should be able to find out everything that they wish about any particular passage or unfamiliar term. If they are working with sources from the World Languages section, especially if they are working with a language that they are still mastering, they need to be able to ask questions about particular words and phrases.

Contextualized reading – In some cases, introductions and annotations are available to shed light upon particular passages or documents but these are only a starting point. Patrons need to be able to see materials that are relevant to every word, to every person, place, and organization, and to every topic that they encounter in any passage.

Customization and personalization – when more contextualizing data is available patrons need to be able to filter that information based upon explicit parameters they choose (customization) or have a system in place that automatically infers what is most important to them based on their past behavior (personalization).

Curation and annotation – Open source collections already contain millions of public domain textual sources for the human record and far more images of people, places, art works, and other subjects. The DPLA must not only provide content to, but must also depend upon content from its users – there just are not enough advanced researchers and library professionals to actively curate all the content that is already available. We must enlist student researchers and citizen scholars, ultimately from around the world to make what is already available increasingly useful. Tasks range from correction of OCR errors and automatically identified people and places through explanatory annotations to original research on broader topics that shed light upon content in the DPLA.

Publication and preservation services – Publication and preservation are complementary services that address the here-and-now and the future (or the synchronic and diachronic). A DPLA has the potential to offer a publication space that can provide patrons of more than 130,000 public, school and academic libraries in the US immediate access, physical and intellectual, to an extraordinary and growing portion of the human record and that can preserve its contents for generations to come.

No system exists that addresses all of the services described above, but the foundations for the integrated set of services exist. An intensive 18-month development period could create a recognizable prototype for the services within a DPLA. Some (but by no means all!) possible contributors follow.

The Perseus Digital Library (http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/) is best known for its holdings on Greco-Roman culture but it also supports collections on Shakespeare and Early Modern England, 19th century American history (with a particular focus upon the Civil War and on local history), and a growing collection of Arabic poetry and literature. Perseus also developed an original actively curated collection for the art and archaeology of the Greco-Roman world, featuring over 60,000 images, and is now collaborating with the DAI in developing a comprehensive collection to explore Greco-Roman culture. The Perseus model thus has been applied to collections from the ancient world through the present and to visual as well as material cultures.

The Perseus Hopper (http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/opensource) provides an extensible, open source framework, developed over twenty years, that manages the Perseus Digital Library and a significant user community (7.5 million visits and 81 million page views in the past 12 months), drawn in roughly equal parts from academia and from the general public. Its services have evolved in response to user needs for particular forms of searching and for working with multiple languages. The Perseus Hopper provides specialized services, developed in response to the needs of established communities, for searching texts and objects, working with multiple languages, and contextualized reading.

At the core of the Perseus Digital Library stands a catalogue that represents the logical structures of documents rather than the physical form of the bound volume.

Figure 8: The Perseus Digital Library. The screenshot to the left illustrates a scalable catalogue that describes content (rather than bound books) and that lists resources available for a dynamically configurable chunk of the Odyssey of Homer. One translation is open but the reader can select other translations, commentaries, a Greek text, names of people and places from this section, and other resources (often reference works) that cite this particular section of the poem. Readers can find information about the Odyssey as a whole, about the books describing Odysseus’ wanderings among gods and monsters, about a particular scene, or about a particular phrase.

The left side of Figure 8 above builds upon canonical citations that have been extracted from various digitized sources but similar results can be obtained with automated methods that identify where works are quoted (with or without attribution). Techniques not only exist that can line up different versions of the same work in the same language but also when a work has been translated into multiple different languages (Bamman, Babeu and Crane 2010).

The right hand side of Figure 8 illustrates a different approach to a catalogue based upon automatic analysis of content, topic modeling. David Mimno and his advisor Andrew McCallum automatically identified topics in an early 20th century textbook of American History and then identified other works from a sample of 10,000 public domain books (Mimno and McCallum 2007).

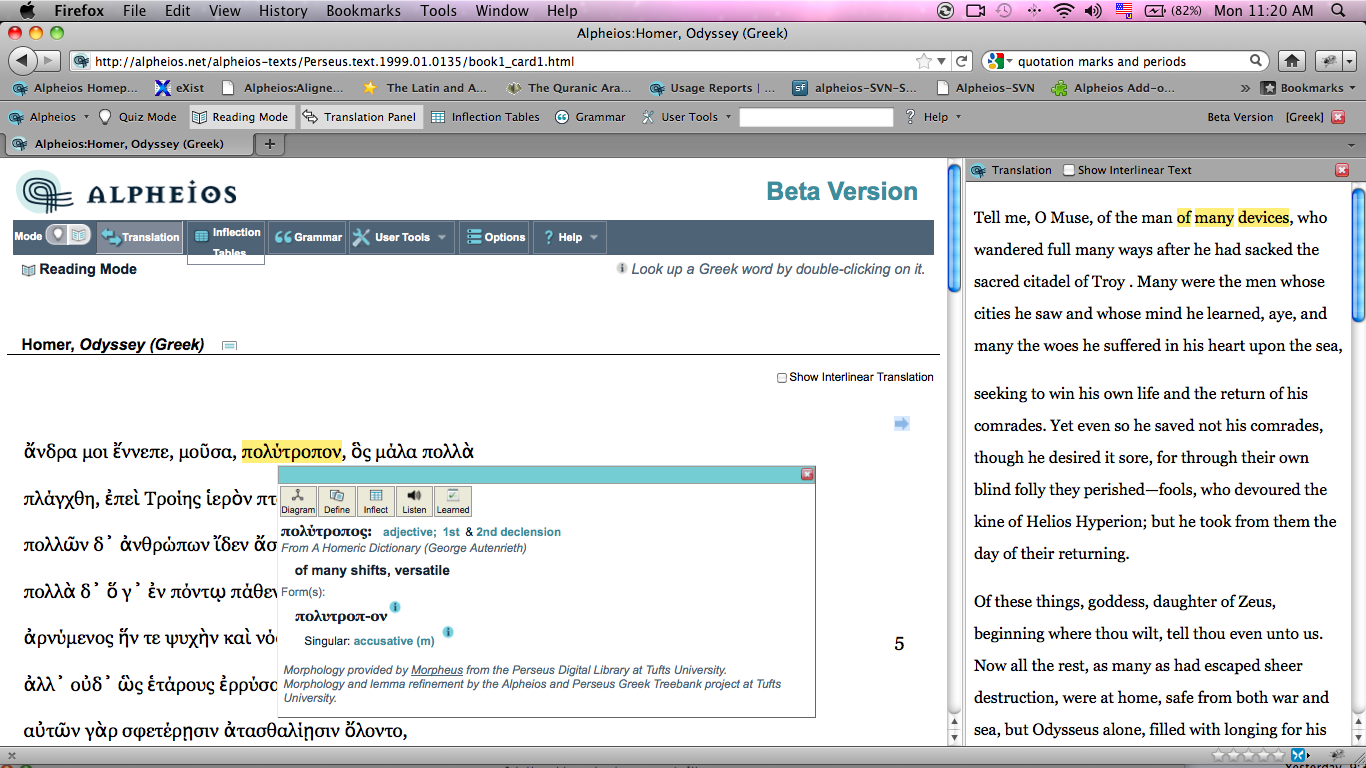

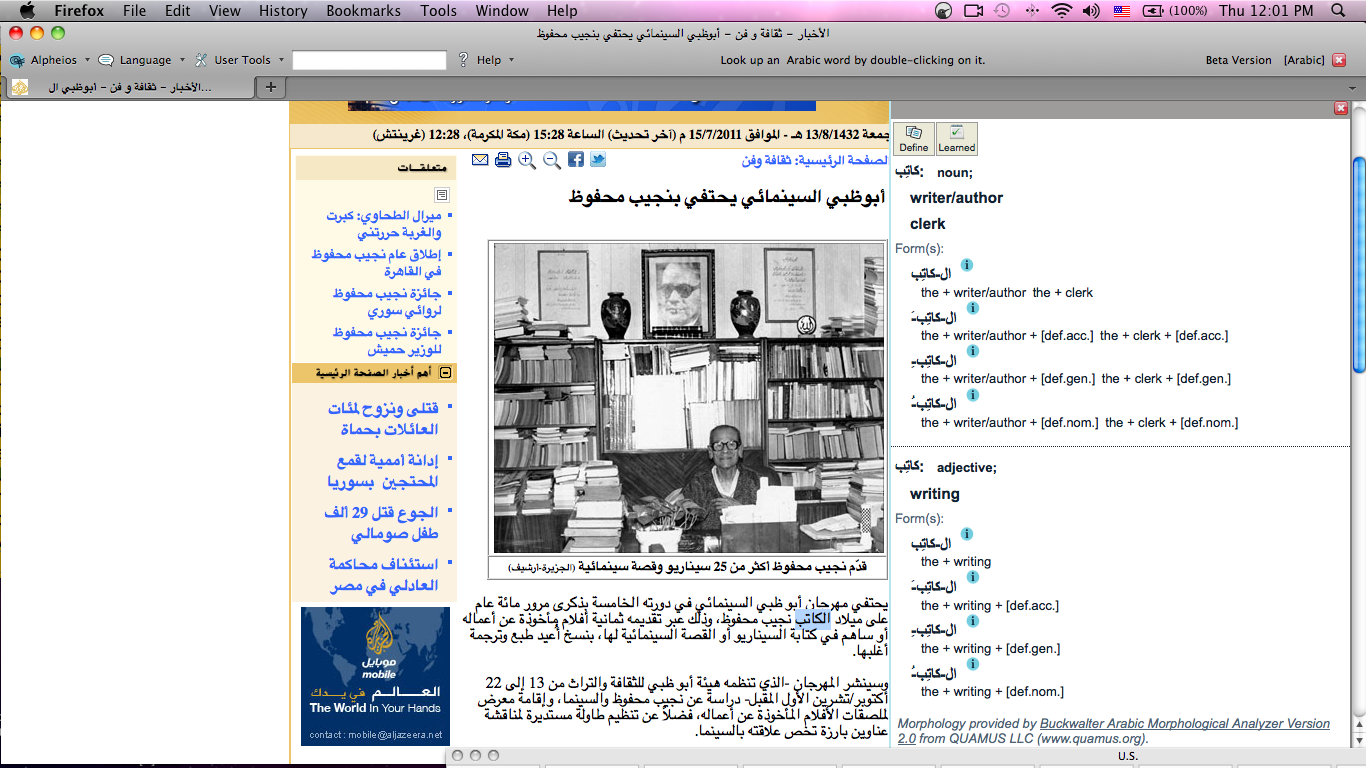

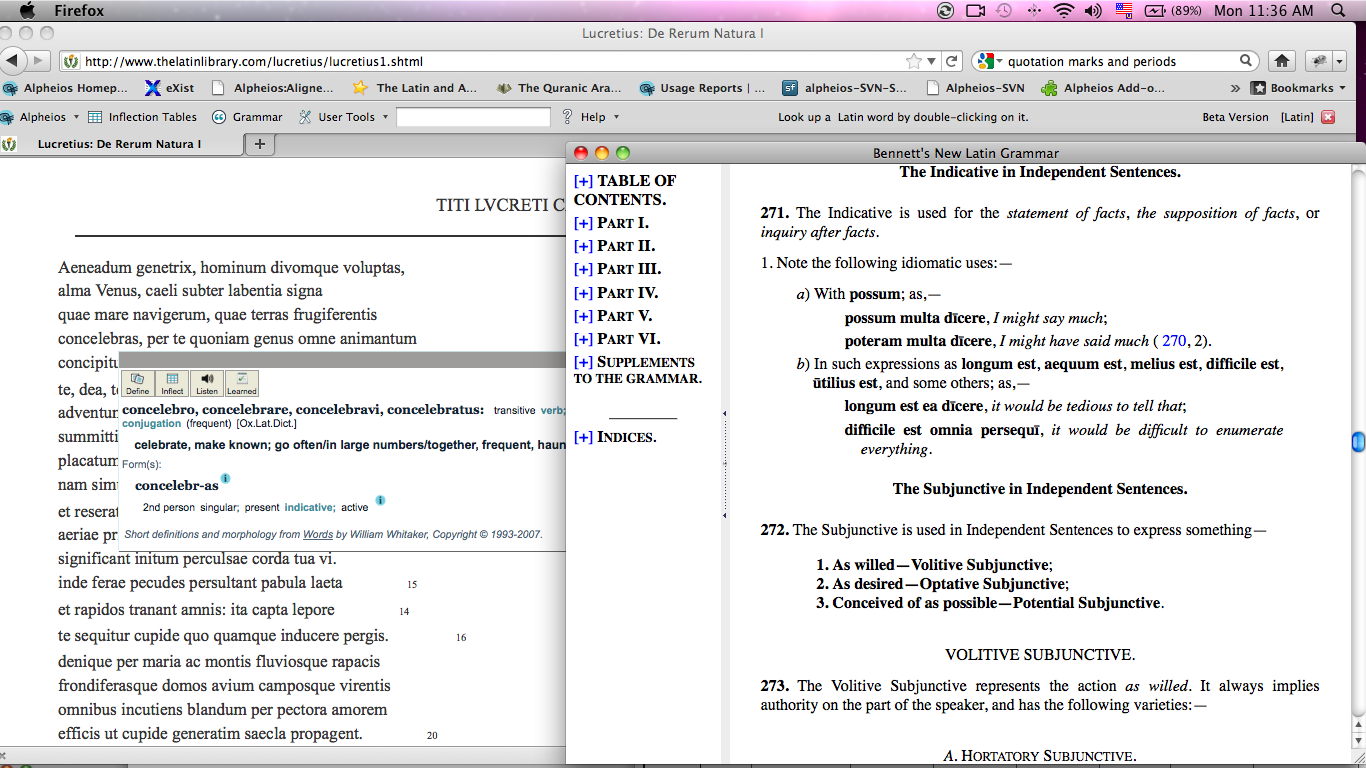

The Alpheios Project (http://alpheios.net) applies expertise developed within the area of medical informatics (several of the principle collaborators worked together at Ovid Technologies (http://ovid.com) to provide enhanced reading tools for those working with foreign language materials, especially historical languages for which commercial resources are scarce.

Figure 9: Reading support in the Alpheios environment. This figure illustrates two forms of reading support. On the left a reader has scrolled over a word in a Greek text and the corresponding English translation is highlighted. The dictionary entry and grammatical function of the word are also illustrated. Both the alignment of source and translation and the linguistic analysis were automatically generated. In each case, Alpheios has provided tools whereby users can correct and expand upon the initial automated results.

Figure 10: Alpheios Reading Environment. The reading environment loaded with Arabic textual materials.

The left side of Figure 10 illustrates dynamic vocabulary support for a reader of Arabic. The system can be customized to the vocabulary and interests of a particular reader, identifying only words that the reader has not yet seen and then prioritizing these for study. On the right grammatical support for a reader of Latin is provided, a function relevant to 170,000 K-12 students of Latin who depend upon public and school libraries, but the general framework is applicable to any language.

Scaling services from thousands to millions of documents is a non-trivial task. The Mining a Million Books Project (http://ciir.cs.umass.edu/research/massivedata/) is a four-year effort funded by the National Science Foundation that is led by the Center for Intelligent Information Retrieval at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst (UMass). This project has been developing new methods for OCR, linguistic and structure analysis, for named entity identification, for the development of collections customized for particular users and for fast, expanded search. The UMass team provides links to leading developments within various branches of computer science, providing expertise about both the most effective methods and about techniques that can scale up to something as large as the DPLA.

Digitized catalogues, scanned pages, and OCR-generated text constitute only a first – and relatively simple – phase of digital sources. Text Encoding Initiative (TEI XML) is a major next step, but far more will be necessary as we integrate many forms of linguistic annotation and general datasets with archaeological and art historical data. The repositories that have emerged in the early twenty-first century have not shown an ability to work with such complex data. The DPLA will need partners who have experience in working with complex data sets and who also have a commitment to the Humanities. The Data Conversancy (http://dataconservancy.org/) developed under the leadership of Johns Hopkins University, provides one example of such an organization, with long term experience in, and commitment to, both scientific and humanities data sets. The Data Conservancy can establish a framework that can manage disparate contributions by advanced scholars and library professionals, student researchers and citizen scholars.

A number of efforts have emerged to support collaborative creation of content. The Wikimedia space is probably best known, with particular projects such as Wikisource.org illustrating how communities can perform basic curation tasks such as the clean up and basic tagging of OCR-generated texts.

Various communities have more distinct needs that Wikimedia projects do not yet address. Native American communities, for example, need to manage a wide range of permissions that reflect their cultural practices. The Mukurtu project (http://www.mukurtuarchive.org/) provides a content management system in which indigenous communities can distinguish content that they can release under a Creative Commons open license from materials that are only appropriate for particular lineages or groups within their communities. The History Engine (http://historyengine.richmond.edu/) gives students the opportunity to learn history by doing the work—researching, writing, and publishing—of a historian. The result is an ever-growing collection of historical articles or "episodes" that paints a wide-ranging portrait of life in the United States throughout its history and that is available to scholars, teachers, and the general public in their online database.

Figure 11: The Mukurtu Project and The History Engine.

Other projects were designed for more academic audiences. The Son of Suda Online editing environment (http://papyri.info/editor/) evolved to support an open-ended set of contributors working with ancient documents preserved on papyrus as they create carefully tagged digital editions following a demanding variant of TEI XML developed for ancient documents (EpiDoc). The initial audience for this service consisted of advanced scholars but key contributors have emerged from beyond academia (the most productive contributor is a retired school teacher). Similarly, 18thConnect (http://www.18thconnect.org) has developed a system to support distributed correction of 18th century sources (which offer distinctive challenges such as the long –s which looks like an ‘f’).

We can contribute by helping (1) to organize meetings of stakeholders (a process that must begin as soon as possible, with follow-up meetings as often as is practicable during the 18 month prototype), (2) to identify developers, (3) to coordinate teaching activities (there is a possibility of customizing winter 2012 classes to begin interacting with and contributing to a DPLA, with an opportunity for a major push with student interns around the country in summer 2012, and second generation classes in the fall); (4) to provide and identify curated collections upon which many communities – Civil War, local history, the ancient world, 18th century, etc. – can build.

Communities: The DPLA must actively seek out many different perspectives. One particular meeting might bring together very different communities of knowledge associated with particular production environments. To what extent can the DPLA provide them with a shared (and more sustainable) infrastructure? What are their distinct needs and aspirations? This meeting should particularly include Native American communities (with users of Mukurtu and of the Native American Archives Protocols as an initial group) and should create a dialogue with popular efforts (e.g., Wikisource and other Wikimedia activities), K-12 (the History Engine), higher education (e.g., Son of Suda Online and 18thConnect), and local history (e.g., the “Tales from the Crypt” and Headstone Stories projects in Mississippi).

Developers: We recommend bringing together the library professionals from the Data Conservancy at Johns Hopkins University, the industry developers associated with Alpheios, and Computer Scientists at UMass, Princeton University and Carnegie Mellon University with a commitment to the DPLA. These should, where possible, correspond with the community representatives.

Collections: Perseus, the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW), the DAI, the Center for Hellenic Studies, the University of Richmond, 18thConnect.

Projects to leverage: A number of efforts are already underway which can (1) already contribute to the DPLA and/or (2) provide a framework that the DPLA can augment, increasing the return on an investment in a prototype.

The Services section (above) listed a number of these projects. To these we add two NEH-funded Institutes for Advanced Topics in the Digital Humanities, each of which is committed to advancing open source content and serving a broad audience. At the least, the curricula for these institutes could be repurposed for a DPLA next summer.

The first institute, entitled the “Linked Ancient World Data Institute”, will be directed by Thomas Elliott and will include a “two year series of summer seminars” hosted by New York University and Drew University. These seminars will involve scholars in the humanities, advanced graduate students, and library and museum professionals and will explore the “possibilities of the Linked Open Data model for use in humanities scholarship with a particular focus on Ancient Mediterranean and Near East studies.”

The second institute will be hosted by Tufts University with project director Gregory Crane. This project, entitled, “Working with Text in a Digital Age,” will include a three-week institute in the summer of 2012 at Tufts with follow up activities over the course of the next year. The institute will focus on “the use of computational and corpus linguistics methodologies for scholarly research for humanities scholars, library professionals, and graduate students.”

Bamman, David, Alison Babeu, and Gregory Crane. "Transferring Structural Markup Across Translations Using Multilingual Alignment and Projection." JCDL '10: Proceedings of the 10th annual joint conference on Digital libraries. New York, NY, USA: ACM, 2010, 11-20.

Mimno, David and Andrew McCallum. "Organizing the OCA: Learning Faceted Subjects from a Library of Digital Books." JCDL '07: Proceedings of the 7th ACM/IEEE-CS joint conference on Digital libraries. New York, NY, USA: ACM, 2007, 376-385.